Euler’s Equation and the Bernoulli Equation (pp. 91-96)¶

Here we will start with the Euler equation and from a sequence of plausible stipulations arrive at the Bernoulli Equation. This development is an alternative to the way most books present the Bernoulli Equation - choose whichever makes more sense to you.

Recall Euler’s equation of motion for a fluid (behaving as a rigid body):

Two “classical” ways to use are illustrated below using

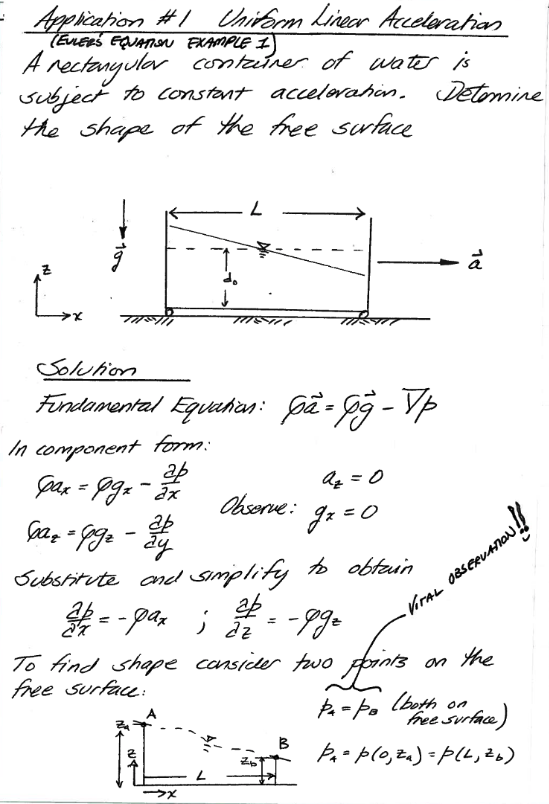

Uniform linear acceleration

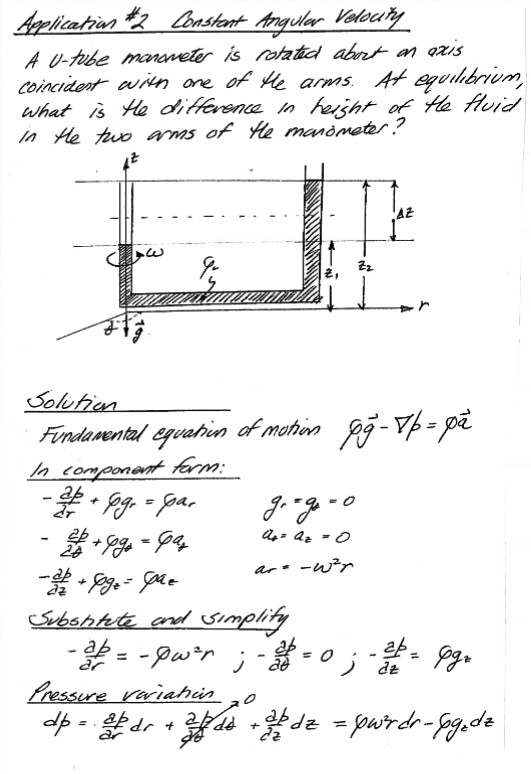

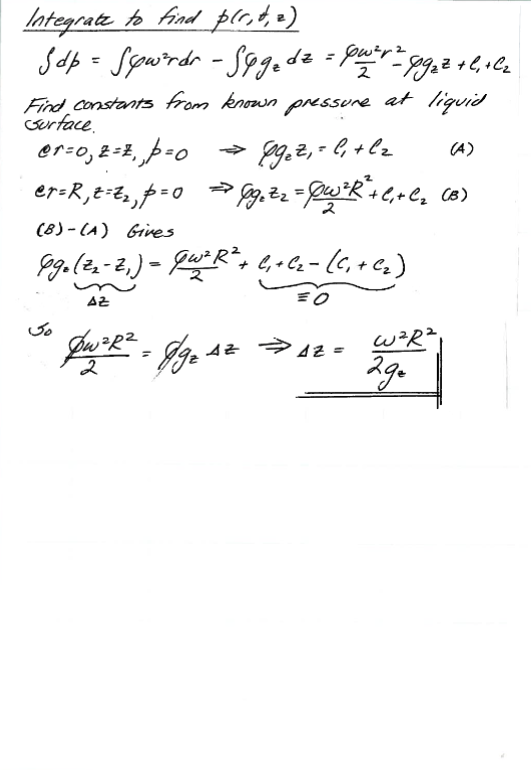

Constant angular velocity

Example: Fluid surface under constant linear acceleration (pp. 91)¶

Here is an example combining hydrostatic pressure equation and acceleration. Identify the problem solving steps depicted.

Derivation of Bernoulli’s Equation from Euler’s Equation¶

Now to continue to onward to the Bernoulli Equation; what appears herein is more of a plausibility argument than a proper derivation, however the goal is to illustrate the relationship of the two. The textbook has an entirely different approach to accomplish the same task, and choose the explaination that makes the most sense to you, and helps you remember how to use the results better.

Starting with Euler’s Equation, and neglect viscous forces (no internal shear) we have:

Stipulate that \(\bar g = -g \bar k\) (we are simply stating that +z is up!)

Next we will require that \(\rho g =\text{constant}\) (incompressible fluid!) which allows

and simplified becomes

Now write \(\bar a\) in differential form (Eulerian reference system); as a set of cartesian component equations we have:

Next we will consider steady flow only which will cause the local acceleration terms to vanish that is:

Make the necessary substitution and simplifications and express the vector equation as a set of component equations as

Next we will stipulate that the flow is irrotational (we will study rotation soon) for the time being, irrotational means that the curl of the velocity field is zero. Typical notation is

notice the capital \(\bar V\), this is the vector field function that provides the components \((u,v,w)\) at any location and time.

If \( curl(\bar V) = \bar 0 \) then the following relationships hold:

So we will make these substitutions to obtain

Now recall that \(y\frac{\partial y}{\partial x} = \frac{1}{2}\frac{\partial y^2}{\partial x}\) and apply this rule on the expressions on the left side of the equation set;

Rearrange as

The sum \(u^2+v^2+w^2\) is simply the magnitude of the velocity vector (speed) at a point squared; so we will simply make that substitution as:

Now recall that \(\frac{dy}{dx} = 0\) if \(y\) is a constant with respect to \(x\). Thus all three equations must equal the same constant.

So anywhere in our flow field (that satisfies all the stipulations and assumptions) we have

where \(C\) is some constant (its often called the total head - but that’s getting ahead of ourselves!)

Often the equation is written along a streamline where in the absence of friction the constant is unchanging and we would have

This is the most useful form of Bernoulli’s equation, where the subscripts \(_1\) and \(_2\) indicate different locations on the streamline.

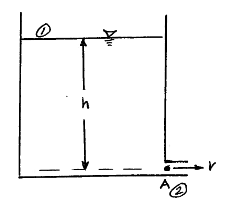

Example: Application of Bernoulli’s Equation¶

A tank with water drains through a small hole to the atmosphere as shown. The depth in the tank is maintained by external addition of fluid.

Determine the speed of the flow in the small hole.

Known

pressure at free surface and at the exit jet

depth in the tank

Unknown

speed of the jet in the exit hole

Governing Principles

Bernoulli’s equation

Assume inviscid, irrotational flow

Solution

Pressure at surface and jet are the same so they cancel. The make-up fluid in problem statement implies the velocity at point 1 is negligible. We can choose to set the jet elevation to zero. Thus the free surface elevation is \(z_1=H\)

So all that remains in the equation is

Solving for \(V\) we have

Example: Application of Bernoulli’s Equation¶

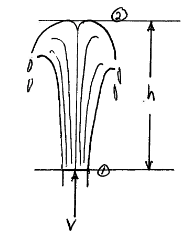

Water issues vertically from a fountain. The water velocity at the exit is 20 feet per second. Assuming irrotational flow, how high will the fountain rise?

Known

pressure at apogee of fountain stream (location 2)

velocity at the exit (location 1)

elevation of the exit (location 1)

Unknown

elevation of the apogee of the fountain stream (location 2)

Governing Principles

Bernoulli’s equation

Assume inviscid, irrotational flow

Solution

Pressure at apogee and jet are the same (assume jet has small cross section; it is atmospheric just after exiting) so they cancel. We can choose to set the jet elevation to zero. At the apogee, the fountain stream has zero velocity just before it begins its fall back to earth.

So all that remains in the equation is

If we desire a numerical result, we simply use our Jupyter Notebook

jet_velocity = 20 #feet/second

gravity = 32.2 #ft/second/second

jet_height = jet_velocity**2/(2.0*gravity)

print("Fountain height is",round(jet_height,3)," feet")

Fountain height is 6.211 feet