Dimensions and Units (pp. 6-8)¶

Dimensions are things that can be measured such as:

length

weight

temperature

speed

time

Most things are expressed in a set of primary dimensions defined either by

length-mass-acceleration or

length-weight-acceleration

Primary dimensions are used to construct secondary dimensions. These secondary dimensions are often more practical in engineering

Units are how much of a dimension is measured or counted.

A meter is a unit of length

Consistent units is a set of units with conversion factors equal to unity. The U.S. Customary (Imperial) is conststent as is the SI (System Internationale), but mixing systems leads to spectular errors (the Hubble Telescope comes to mind!). Using a single system, when possible, reduces errors because of fewer arithmetic operations. Many practical cases commonly use blends of both systems so unit conversions are required. The problem solving format example contained embedded conversions.

Cancelling, carrying, and converting units¶

Vital in most engineering applications; results of calculations need to be in useful units - but should use primary units so that errors can be detected and quickly repaired, and dimensional homogenity can be checked

Note

Many practical formulas are “empirical” and the resulting equations are not dimensionally homogeneous; expecting dimensional homogenity using these is absurd - don’t even try. A common example from hydrology is something called the rational runoff formula. It looks like

\(Q_p = CiA\)

where the various terms are in the following explicit units:

\(Q_p\) is discharge in cubic feet per second

\(C\) is the runoff coefficient (essentially dimensionless)

\(i\) is rainfall intensity in inches per hour

\(A\) is drainage area in acres.

In this formula, converting units is a mistake and the results won’t make sense - don’t even bother. We still use the formula because it has practical value and there has never been much motivation to pursue its equivalent in a dimensionally homogeneous fashion.

The textbook calls its unit conversion method the grid method; the idea is simple enough; express original quantity in its units and use unit conversions to produce a desired practical unit. Consider the example that follows

Example Unit Conversion

A 20 lb-m projectile is to be accelerated at 100\(ft/s^2\). What force is required?

State the problem

What force is required to accelerate a 20 lb-m projectile at 100\(ft/s^2\)?

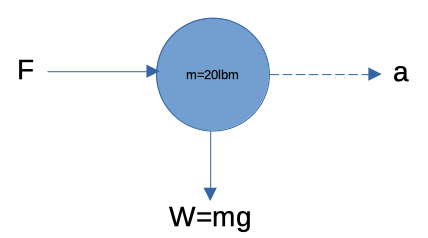

Sketch the situation

List known quantities

\(m=20~lbm\) (note that pounds mass is a unit of mass, not weight in the usual sense)

\(a= 100~ft/s^2\)

List unknown quantities

\(F\) the requires force (acting as shown, if we were accelerating upward would need to consider gravity)

Identify and list governing principles, assumptions, and equations

\(\bar F = m \bar a\)

Analyse the problem - solve for the unknowns

\(F_x = m a_x = (20~lbm)(100~ft/s^2)\)

mass = 20 #mass in pounds-mass

acceleration = 100 #in ft/s/s

force = mass*acceleration

print("Applied force is",round(force,2),"lbm-ft/s^2")

Applied force is 2000 lbm-ft/s^2

Discuss the results

Notice the numerical result, the answer is correct but not in useful units, but by the unit conversion

\(1~lbf=1~lbm \cdot g\) we can obtain a useful result in pounds force.

The conversion is \(2000~\frac{lbm-ft}{s^2} \cdot \frac{1~lbf}{1~lbm \cdot g}\)

grabity = 32.2 #gravitational acceleration in US customary units

force = force*(1.0/(1.0*grabity))

print("Applied force is",round(force,2),"lbf")

Applied force is 62.11 lbf

So if the 20 lbm mass is acted upon by a 62.11 lbf, it is anticipated that it will accelerate at a rate of 100 \(ft/s^2\) (until the force is removed).

Note

A pound mass is a very archaic unit, and used herein to illustrate unit conversions. Learn more at Shedding those Pounds!