Pressure Force on Submerged Objects (pp 64-78)¶

Now we consider the forces generated on submerged objects by hydrostatic pressure.

It’s the same force you feel on your 耳 when you dive to the bottom of a schwimmbad.

Note

I am having a little fun with the language translators on Google; the sentence in English is “… It’s the same force you feel on your ears when you dive to the bottom of a swimming pool”.

Uniform Pressure¶

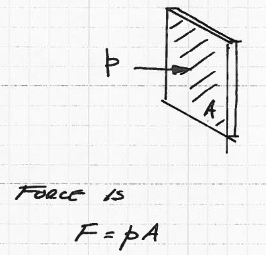

Consider area \(A\) shown with uniform pressure as shown on Fig. 63

Fig. 63 Pressure force on some area.¶

The indicated force is the product of the area \(A\) and the pressure \(p\)

Distributed Pressure¶

Now, consider the area \(A\) shown with distributed pressure as shown on Fig. 64. As we move around the plate, the value of \(p\) changes with position (like going down in a column of water)

Fig. 64 Pressure force on a small area in a variable pressure field¶

In this instance, we use calculus to integrate all the little forces fo fine the aggregate (net) force on the entire plate.

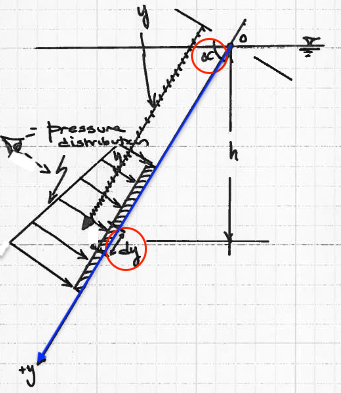

Now lets extend the idea, to an arbitrary angle in the distributed pressure field, as in Fig. 65

Fig. 65 Flat plate submerged at an arbitrary angle¶

Depth to an incremental portion of the plate \(dy\) is \(h\). Distance along the \(+y\) axis is \(y\). The value of \(y\) is related to depth, \(h\), by the angle \(\alpha\).

Note

We choose \(\alpha\) to represent the angle because it looks like a fish, and fish are found underwater!

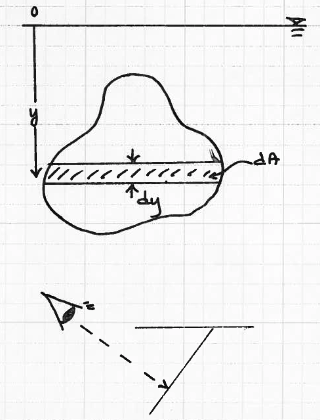

Next looking at the plate from a viewing angle that is normal to the plate (the eyeball in the sketch)it might look like Fig. 66

Fig. 66 Looking perpindicular to the flat plate. Width of the integrand is some function of \(y\)¶

In this sketch the panel area is \(dA = width(y) \cdot dy\) when looking perpindicular to the \(+y\) axis. The resultant net force on the submerged plate (perpindicular to the \(y\) axis) is simply

Now we apply some geometry and triggernometry to relate the integral to depth (and some moments).

Fig. 67 Geometric/Trigonometric relationships.¶

Generally we will want to express pressure in terms of \(y\) or \(h\).

In practice the actual integration is a nusicance, instead we would likw to be able to deal in total area and depth. The term in the red box is the first moment of area that you had in statics.

Note

The observation of that the red box is the 1st moment of area, makes those tables of centroids and such for common geometric shapes quite useful in fluids!

If you recall from statics, the first moment of area is the distance to the centroid of the geometric object from the axis (in this case the \(x\) axis that is trying to poke your eye!)

Applying some trigonometry and algebraic substitution

Where \(\bar h\) is the depth from the free surface to the centroid of the plate area. So we now can express the magnitude of the force in terms of depth (to the centroid) and the plate area.