Dispersion¶

In actual releases of pollutants into the environment advection based on mean section velocity computations/measurements and diffusion cannot explain observed behavior. As an example, consider the release of smoke particles (0.1 m) on the left coast of the USA (California) into a westerly wind (wind blowing from west to east) at a speed of 5 meters/sec. Assuming a transcontinental trip, one would expect a spreading of the smoke particles of less than 4 cm over a distance of 5000 meters – thus these two processes alone cannot explain actual behavior.

In actual flows, speeds (velocities) are neither uniform nor steady – the mixing caused by non-uniform flows is called dispersion. Dispersion is a consequence, in modeling, of not being able to accurately describe the velocity field at a small enough scale spatially and temporally to account for the continuous changes in directions and speeds that occurs in real flows. (Read any fluid mechanics textbook – especially the section on turbulent correlation coefficients). There are several processes that arise in fluid flow modeling and measurements that can be called dispersion: shear-induced dispersion; turbulent diffusion; hydrodynamic dispersion.

Shear-Induced Dispersion (Pipe and Open Flows)¶

Shear-induced dispersion occurs in a flow field where the fluid velocity varies with position in a direction perpendicular to the mean section velocity. If contaminant concentrations in a shearing flow field vary in the direction of mean flow, then a dispersive mixing phenomenon will be observed, producing a net transport of pollutants from regions of high concentration to low concentration.

Typically a Fickian-type model using the section average concentration is used to explain shear-induced dispersion. The diffusion coefficient is called the shear-flow dispersivity.

The dispersivity is often estimated from a ratio of velocity variation and a characteristic mixing length based on the dimensions of the flow field.

Turbulent Diffusion (Pipe and Open Flows)¶

Most flows are turbulent – often we model the flows using ideal (laminar) flow theories and use turbulent flow equations of motion to determine mean velocity values, and turbulent flow variation models to explain the random nature of fluctuations about the mean flow values. In many cases the fluctuations themselves are uninteresting, but their effect on mixing is critical. The mixing caused by the turbulent variations in speed and direction is called turbulent diffusion.

Again a Fickian type model is used, but the point concentration replaces the section average concentration

In three dimensions the flux is represented as (isotropic representation – off diagional terms are not necessarily zero)

The diffusion coefficients are known as turbulent diffusion coefficients, or eddy diffusivities. The values of eddy diffusivity vary in space, time, and direction. They are strongly dependent on the nature of the flow field (related to velocity at any location). Closure models (correlations between geometry, flow speed, and eddy diffusivities) are still incomplete, although for many flow systems good predictions are possible.

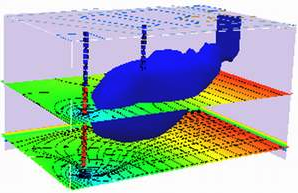

Hydrodynamic Dispersion (Porous Flows)¶

Conceptually hydrodynamic dispersion is similar to shear-induced dispersion in pipe and open flows. It occurs because of sectional velocity variation at the pore scale and because of macroscopic flow variation because of medium non-homogeneity. It is not a consequence of turbulence because it occurs even in laminar flows in porous media. Again the working model is a Fickian type model:

In hydrodynamic dispersion the diffusion coefficients are called hydrodynamic dispersion coefficients and are directly proportional to the local average linear velocity.

Summary¶

Dispersion is a mixing process that is modeled using a model that is structurally identical to diffusion. The dispersion coefficients are dependent on the flow field for both magnitude and direction. The dispersion coefficients in most flows are orders of magnitude larger than diffusion coefficients making their accurate representation critical for good predictive modeling of pollutant transport. To model pollutant transport one must first determine the nature of the flow (velocity) field – thus in this course we will devote a great deal of effort in determing flow and discharge characteristics before trying to move pollutants in the flow field.