Modeling Advection¶

Modeling advective transport in groundwater is a critical component of hydrogeology and environmental science, as it allows us to understand and predict the movement of contaminants and the transport of solutes through subsurface aquifers. Advective transport refers to the bulk movement of water and the substances it carries, driven primarily by hydraulic gradients and pressure differences within the groundwater system. This process plays a fundamental role in determining the fate and transport of pollutants, nutrients, and other substances in the subsurface environment.

A variety of widely used methods and techniques are used; These methodologies are essential for comprehending the dynamics of groundwater flow and the transport of substances within aquifers. Two popular methods for modeling advective transport in groundwater are numerical modeling and analytical solutions.

Numerical modeling stands as a cornerstone in the field, with models like MODFLOW (MODular Finite-Difference Ground-Water Flow Model) at the forefront. Numerical models divide the subsurface into discrete grid cells, considering various factors such as hydraulic conductivity, boundary conditions, and aquifer heterogeneity. These models utilize numerical algorithms to simulate the behavior of groundwater flow and contaminant transport over time. By incorporating data from field investigations, they enable scientists to make accurate predictions regarding the movement and fate of contaminants in complex geological settings. Numerical models are exceptionally versatile and can handle a wide range of scenarios, making them an indispensable tool for hydrogeologists and environmental scientists.

On the other hand, analytical solutions offer a more simplified approach for specific scenarios. These solutions are often employed when dealing with idealized geometries and boundary conditions. For instance, the advection-dispersion equation, a fundamental equation in groundwater transport, can be solved analytically for simple scenarios. Analytical solutions provide quick insights into transport phenomena and are valuable for initial assessments and educational purposes. However, they may not capture the complexities of real-world aquifers as effectively as numerical models.

Methods¶

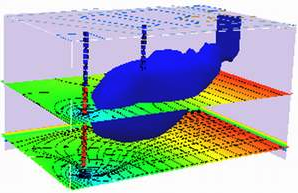

A reductionist point of view lets us categorize practical modeling methods into two categories: particle (parcel) tracking and eulerian finite- difference,element, or volume methods (marker-in-cell is a hybrid). The Eulerian methods almost always employ some kind of flux limiter to maintain proper mass balances, upwinding is one such approach. Particle tracking and upwind finite difference approaches are two distinct methods for modeling advective transport in groundwater, each with its own set of advantages and limitations. Let’s compare and contrast these approaches:

Particle Tracking:¶

Conceptual Approach: Particle tracking models simulate the movement of individual particles within the groundwater flow field. This approach provides a more intuitive understanding of how contaminants or solutes move through the subsurface.

Accuracy in Complex Flow: Particle tracking is well-suited for modeling complex groundwater flow scenarios, such as in fractured aquifers or regions with varying flow directions. It can accurately represent irregular flow patterns.

Limitations: However, particle tracking may become computationally intensive when modeling a large number of particles over extended periods, making it less practical for long-term simulations.

Adaptive Resolution: It allows for adaptive grid refinement, where particles can be concentrated in regions of interest, offering higher resolution where needed.

Lagrangian Approach: It follows the Lagrangian approach, where particles move with the flow, which can be advantageous for understanding transport phenomena from a particle’s perspective.

Upwind Finite Difference:¶

Grid-Based Approach: Upwind finite difference methods are grid-based, where the domain is divided into grid cells, and equations are solved at discrete locations within each cell.

Computational Efficiency: Upwind finite difference methods are computationally efficient for large-scale models and long-term simulations. They are widely used for regional-scale groundwater flow and transport modeling.

Stability: They are known for their numerical stability, which ensures that the solution remains accurate even when using relatively large time steps.

Accuracy in Uniform Flow: Upwind finite difference methods may perform very well in uniform flow conditions, but they can encounter challenges in accurately representing complex flow patterns, especially in situations where there are rapid changes in flow directions.

Eulerian Approach: These methods follow an Eulerian approach, where flow and transport equations are solved at fixed grid locations, making them less intuitive from a particle’s perspective.

In summary, the choice between particle tracking and upwind finite difference approaches for modeling advective transport in groundwater depends on the specific characteristics of the groundwater system and the research objectives:

Particle tracking is preferred for understanding transport at a detailed, particle-level scale and for modeling complex flow patterns.

Upwind finite difference methods are suitable for large-scale, long-term simulations where computational efficiency and stability are essential, especially in cases of relatively uniform flow.

Often, a combination of both methods may be employed in a modeling study to take advantage of their respective strengths, using particle tracking for detailed insights in specific areas and upwind finite difference methods for broader-scale simulations.

The remainder of this notebook presents simple examples of each method.

Note

While the methods in this notebook would be fine, practical “for money” modeling will usually employ specialized software; especially if lawyers will somehow get involved.

To build models, we simply apply the Reynolds Transport Theorem to the advective flux component to produce something like: