Reactive Transport#

Reactive constituent transport in groundwater refers to the complex movement and transformation of dissolved substances as they migrate through the subsurface environment. This phenomenon is characterized by the interaction of these constituents with the surrounding geological materials and the potential for chemical reactions to occur, altering the composition of the groundwater. It plays a critical role in environmental processes, as it encompasses the transport of contaminants, nutrients, and other solutes, often involving reactions such as sorption, degradation, precipitation, and dissolution. Understanding reactive constituent transport is essential for managing and mitigating groundwater contamination, optimizing groundwater remediation strategies, and safeguarding the quality of groundwater resources.

Reactions#

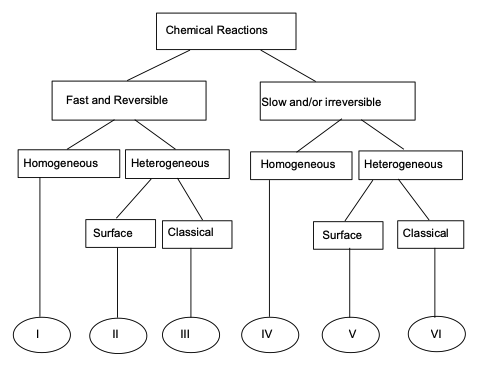

In groundwater systems, chemical reactions play a crucial role in determining the fate and transport of contaminants. These reactions influence how contaminants move, transform, and potentially degrade as they interact with water, soil, and rock matrices. The nature of these reactions—whether fast or slow, reversible or irreversible, heterogeneous or homogeneous—greatly affects contaminant migration and remediation efforts.

The figure below is a classification of different kinds of reactions (CITE source)

Fast and Slow Reactions#

Chemical reactions in groundwater transport can occur at varying speeds. Fast reactions typically involve the instantaneous equilibrium between chemical species, such as the dissociation of weak acids or the sorption of ions onto mineral surfaces. These reactions are often assumed to occur almost instantaneously relative to groundwater flow, allowing the system to reach equilibrium quickly. For example, carbonate equilibria or ion exchange processes often fall into this category.

On the other hand, slow reactions occur over longer timescales and may limit the overall transport of contaminants. Slow reactions often involve complex chemical transformations, such as the biodegradation of organic contaminants or the precipitation of minerals from solution. In these cases, the reaction kinetics play a critical role in the persistence of pollutants. For example, the biodegradation of hydrocarbons in groundwater often proceeds at a slow rate, influencing long-term contaminant plumes.

Reversible and Irreversible Reactions#

Reversible reactions in groundwater transport involve chemical processes that can proceed in both forward and backward directions. Examples include adsorption-desorption processes, where contaminants attach to and detach from soil particles depending on environmental conditions like pH and ion concentration. These reactions are typically described by equilibrium isotherms, such as the Freundlich or Langmuir models, which allow the contaminant to move back into solution under changing conditions.

In contrast, irreversible reactions proceed in one direction only, leading to permanent transformation or immobilization of contaminants. A common example is the precipitation of metals, such as when dissolved iron reacts with oxygen to form insoluble iron oxides. Irreversible reactions are significant for remediation strategies, as they can permanently remove contaminants from the mobile phase in groundwater, preventing further transport.

Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Reactions#

Homogeneous reactions occur uniformly throughout the aqueous phase and involve dissolved chemical species. For instance, the hydrolysis of an organic contaminant or the dissolution of carbon dioxide in water are homogeneous reactions, as the reaction takes place in a single phase (the water). These reactions are typically modeled using simple kinetic expressions since they involve species that are fully mixed within the groundwater.

In contrast, heterogeneous reactions involve more than one phase, typically occurring at the interface between solid and liquid phases. Examples include adsorption onto soil particles, surface-catalyzed redox reactions, or precipitation and dissolution of minerals. These reactions are spatially localized and depend on surface properties, making them more complex to model. For example, the reduction of nitrate by iron in groundwater is a heterogeneous reaction that occurs at mineral surfaces, with rates dependent on both the surface area available and the chemical composition of the solid phase.

Surface and Classical Reactions#

In groundwater transport, surface reactions differ from classical (bulk) reactions in how they occur and their controlling factors. Surface reactions take place at the interface between solid and liquid phases, such as the adsorption of contaminants onto soil or mineral surfaces, or catalysis of redox reactions on solid substrates. These reactions depend heavily on surface area, mineral composition, and the specific surface chemistry of the material. In contrast, classical reactions occur uniformly throughout the bulk aqueous phase, involving only dissolved species. Examples include hydrolysis or neutralization reactions that occur within the groundwater itself. Surface reactions tend to be slower and more complex, requiring consideration of solid-liquid interactions, while classical reactions can often be described with simpler kinetic models focused solely on chemical concentrations in solution. Surface reactions play a key role in contaminant immobilization and transformation, making them critical for understanding contaminant fate in heterogeneous subsurface environments.

Some surface reactions important in groundwater include:

Adsorbtion - solute clings to surface due to various attractive forces - usually electrostatic.

Ion-Exchange - ions are attracted to mineral surfaces substitute themselves into the mineral structure. Zeolites are examples of natural ion-exchange materials.

Chemisorption - solute is incorporated into a sediment by chemical reaction.

Absorbtion - solute diffuses into solid matrix and clings to interior surfaces. (Notice the “b” replaces the “d” in adsorbtion)

All these reactions are controlled to a great extent by solution pH, EH, and salinity.

References#

OpenAI (2024). Prompt: “Can you help me write a script on chemical reactions as applied to groundwater transport, with focus on fast/slow, reversible/irreverseable, heterogeneous/homogeneous reactions? The audience is first year environmental engineering graduate students. No math please”. ChatGPT-4.0. URL

https://chatgpt.com/c/66f31881-d074-800d-8d7e-62967bbc6717

Note

“The OpenAI URL provided in references helps retrieve specific content shared, but the information is not recoverable unless required by legal obligations.”