Lab 1 - Fluid Properties#

Course Website

Readings#

Videos#

Outline#

Background#

A fluid has certain characteristics by which its physical condition may be described. These characteristics are called properties of the fluid.

Note

Properties help describe the “state” of the system under study. A system is whatever is being studied or analyzed, anything not part of the system is part of the surroundings. The boundary is the imagined surface that separates the system from its surroundings.

Systems are described by specifying values that characterize the system; these values are called properties. A property is a measurable characteristic of a system that depends only on the present conditions within the system (called the state of the system). The state of a system means the conditions of the system as defined by specifying its properties.

Properties can be organized into categories, one of which is material properties; the properties explored in this laboratory are selected material properties of some liquids

Mass Density#

Mass density, or just plain density, denoted by the symbol \(\rho\), is a fundamental property of all substances, including fluids.

It is defined as the mass per unit volume of a material and can be expressed as an equation in words:

Or using Greek letters, mathematically as:

Units: \(\mathrm{kg/m^3}\) (SI), \(\mathrm{lbm/ft^3}\) (FPS).

In the context of fluids, density provides critical insight into how fluids behave under various conditions, such as flow through pipes, buoyancy, and pressure variations with depth.

For instance, the density of water at standard temperature and pressure (STP) is approximately \(1000~kg/m^3\), while air has a much lower density of about \(1.2~kg/m^3\).

Measuring Density of Fluids#

Practical methods to measure the density of a liquid include:

Gravimetric Method

This method involves directly measuring the mass and volume of a liquid sample and using the formula \(\rho = \frac{M}{V}\).

Steps:

Weigh an empty container on a precision scale and record its mass.

Fill the container with the fluid and weigh it again to determine the mass of the fluid (\(M\)).

Measure the volume (\(V\)) of the fluid using a graduated cylinder or volumetric flask.

Calculate the density.

Example:

If \(M=0.25 kg\) and \(V=0.00025 m^3\), the density is:

\(\rho=\frac{0.250~kg}{0.00025~m^3}=1000 kg/m3\)

Hydrometer Method

A hydrometer is a floating instrument calibrated to measure fluid density directly.

Steps:

Submerge the hydrometer in the fluid.

Read the density from the scale where the hydrometer’s surface level aligns with the fluid.

This method is especially useful for liquids like alcohol, brines, and oils.

Pycnometer Method

A pycnometer is a specialized container with a known volume used for highly precise density measurements.

Steps:

Weigh the empty, dry pycnometer.

Fill it with the fluid and weigh it again to determine the mass of the fluid.

Calculate the density using the known volume of the pycnometer.

Note

The pycnometer is clearly a gravimetric technique, but eliminates the need to measure the volume, as the device itself performs this measurement directly

Importance of Density in Fluid Mechanics#

Understanding density is critical for:

Buoyancy Analysis: The density difference between a fluid and a submerged object determines whether it floats or sinks.

Hydrostatics: Density directly influences the pressure variation in a fluid column, P=ρghP=ρgh.

Flow Dynamics: Density is a key parameter in determining the Reynolds number, which predicts flow behavior (laminar or turbulent).

Temperature Matters

At a given temperature and pressure the density of a given liquid is constant. Let us say we keep pouring some liquid into a beaker, as the mass increases so does the volume whereas density, which is the ratio of mass to volume, stays constant.

As such all experimental determinations of density require that the temperature of the liquid be measured.

Accurately measuring and understanding fluid density, informs engineers so they can design systems involving fluid transport, storage, and control.

Specific Weight#

Specific Weight is the weight per unit volume of the material. Remember that weight is a force obtained by multiplying mass and gravitational acceleration (g).

As an equation in words:

or more conventionally

At a given temperature, pressure and location, the specific weight of a fluid is constant. However, the acceleration due to gravity varies slightly with location. The specific weight of a fluid is slightly lower at the poles than at the equator even when the temperature and pressure of the fluid are the same at both locations.

Specific Gravity#

Specific Gravity is another important fluid property that is defined as the ratio of the density of a fluid to the density of water at the same temperature.

Clearly, the specific gravity is equal to 1.0 for water. Fluids denser than water have a specific gravity greater than 1 while those lighter than water have specific gravity less than 1.

Being a ratio of two densities, specific gravity is a dimensionless quantity. Specific gravity can tell us whether an object will float or sink in water. Specific Gravity also provides consistency to compare fluids across different units.

Viscosity#

Viscosity is a measure of a fluid’s resistance to deformation or flow under an applied shear force. It quantifies the internal friction between adjacent layers of fluid that are moving at different velocities. Viscosity plays a central role in fluid mechanics as it affects flow characteristics, energy losses, and the behavior of fluids in engineering systems.

There are two primary types of viscosity:

Dynamic Viscosity (\(\mu\))#

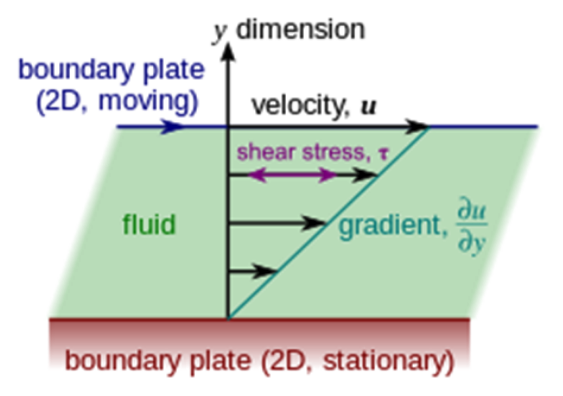

Dynamic viscosity measures the tangential force per unit area (ττ) required to move one fluid layer relative to another at a unit velocity while maintaining a unit distance separation. It follows Newton’s law of viscosity:

\(\tau = \mu \frac{\partial y}{\partial u}\)

Where:

\(\tau\): is the applied shear stress (\(Pa\))

\(\mu\): is the dynamic viscosity (\(Pa \cdot s\))

\(\frac{\partial y}{\partial u}\): is the velocity gradient perpendicular to the flow.

Kinematic Viscosity (\(\nu\))#

Kinematic viscosity is the ratio of dynamic viscosity to fluid density:

\(\nu = \frac{\mu}{\rho}\)

Units: \(m^2/s\) in SI.

Measuring Viscosity#

Several methods can be used to measure viscosity. In this laboratory, we will use on Stoke’s law due to its feasibility, but additional methods are included for context.

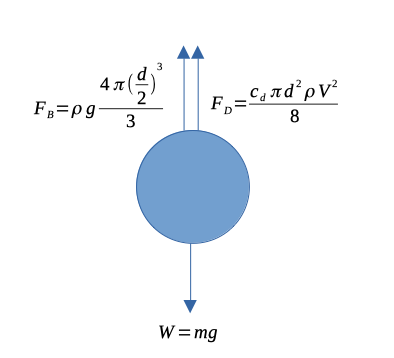

Stoke’s Law (Falling Sphere Method)

Principle: A small sphere is dropped into a fluid, and its terminal velocity (\(u\)) is recorded. Under terminal velocity conditions, the drag force equals the sum of buoyant and gravitational forces. From Stoke’s law, the dynamic viscosity is calculated as:

\(\mu=\frac{2r^2(\rho_s−\rho_f)g}{9u}\)

Where:

\(r\): Sphere radius (mm)

\(\rho_s,\rho_f\): Densities of the sphere and fluid (\(kg/m^3\))

\(g\): Gravitational acceleration (\(m/s^2\))

\(u\): Terminal velocity (\(m/s\))

Setup: Use a tall column of fluid, small spheres, and a stopwatch to measure the sphere’s falling time over a known distance.

Capillary Tube Viscometer

Principle: Measures the time (\(t\)) it takes for a fluid to flow through a capillary under gravity or applied pressure. Viscosity is calculated as:

\(\mu=K \cdot t\)

Where \(K\) is a calibration constant based on the tube’s geometry and fluid properties.

Use: Common for low-viscosity fluids like water and oils.

Rotational Viscometer

Principle: Measures the torque required to rotate an object (e.g., spindle or cylinder) in a fluid at a constant speed. The torque is proportional to the fluid’s viscosity.

Use: Suitable for measuring a wide range of viscosities, including non-Newtonian fluids.

Inclined Plane Method

Principle: A known volume of liquid is released on an inclined plane, and the time it takes to travel a set distance is recorded. The viscosity is inferred from the relationship between time, fluid properties, and inclination angle.

Use: While less precise, this method is a feasible alternative for determining relative viscosities in a laboratory.

Importance of Viscosity in Fluid Mechanics#

Viscosity influences several critical aspects of fluid behavior, including:

Energy Losses: Higher viscosity increases resistance to flow, leading to greater energy dissipation.

Laminar and Turbulent Flow: The Reynolds number, which predicts flow regimes, depends on viscosity.

Practical Applications: From lubrication in machinery to fluid transport in pipelines, viscosity is a key parameter.

Temperature Matters

Viscosity is strongly temperature-dependent. Consider how honey flows more easily when warmed compared to when it’s at room temperature or chilled. Similarly, engine oil thickens in cold weather, making it harder for car engines to start.

As such, all experimental determinations of viscosity require that the temperature of the liquid be measured.

By accurately measuring viscosity, engineers can design efficient systems that minimize losses and optimize performance. In this lab, we will use Stoke’s law to measure the viscosity of different fluids, but the insights extend to various industrial and natural applications.

Viscosity#

Viscosity quantifies the ability of the fluid to resist shear stress (i.e., internal resistance). One can also conceptualize viscosity as the frictional forces that exist between two layers of fluid that are in relative motion.

Dynamic Viscosity measures the tangential force per unit area required to move one horizonal plane relative to another at a unit velocity when maintaining unit distance separation. The shear stress applied causes the fluid to flow (or flow causes stress).

Newton’s law of viscosity states that the shear stress, \(\tau\), is proportional to the velocity gradient (across the flow flow), \(\frac{du}{dy}\) (see Figure 1). Dynamic viscosity ,\(\mu\), is the constant of proportionality.

Newton’s law expressed as an equation is: $\(\tau = \mu \cdot \frac{du}{dy} \)$

thus dynamic viscosity is the ratio of shear force to the velocity gradient. It has units of \( Pa \cdot s = \frac{kg \cdot m}{s^2} \cdot \frac{s}{m^2}\).

In cgs system the units of dynamic viscosity is Poise (or more commonly centipoise, cP).

In US Customary units we express viscosity as \(\frac{lbf}{ft \cdot s}\).

In practical fluid mechanics, we often encounter the ratio of dynamic viscosity to density. This term is the kinematic viscosity.

Expressed as an equation in commonly used notation:

The kinematic viscosity has SI units of $\(\frac{m^2}{s}\)$.

A useful method to determine viscosity of liquids is to record the rate at which a sphere will fall through a liquid of interest. Under equilibrium conditions, the frictional forces experienced by the sphere will be equal to its weight. The sphere will fall at a constant speed known as the terminal velocity. The phenomenon is called Stokes law (or Stokes flow).

A simple force balance is depicted in Figure 2, where the bouyant force and drag force are equal to the weight of the sphere.

Stokes flow occurs at pretty low Reynolds numbers so the laminar correlation for the drag coefficient is appropriate

If the Reynolds number is less than \(\frac{1}{2}\) the drag coefficient is \(c_d = \frac{24}{Re}\), using this representation of drag the force balance for the sphere allows us to solve for velocity, \(u\),

where, g is the acceleration due to gravity, d is the diameter of the sphere, \(\nu\) is the kinematic viscosity, \(\sigma\) is the density of the sphere, \(\rho\) is the density of the fluid.

We can apply the formula to get an idea of how fast to expect a sphere to fall if Stokes flow holds. In the experiment we will use Glycerine as the liquid phase, and small steel spheres the largest is about 2.5 millimeters

‘’’ # Estimate Sphere Falling Speed assuming laminar flow gravity = 9.81 #m/s^2 viscosity = 15.103 # Ns/m^2 density_liquid = (69.5/50)10001000 #kg/m^3 density_sphere = (11.350)10001000 #kg/m^3 diameter = 0.0125 #meters - nominal 2.5mm upper_support_terminal_speed = (gravitydiameter**2)(density_sphere-density_liquid)/(18.0*viscosity) print(“Stokes flow speed limit = “,round(upper_support_terminal_speed,6),” millimeters per second”) ‘’’

So using the above script we conclude that we should be able to make measurements for spheres as large as 25 mm, using a stopwatch and visual observation, our spheres are quite a bit smaller, so we should have no issues.

Laboratory Objectives#

Measure density, specific gravity, and viscosity of various liquids.

Develop an experimental protocol (step-by-step instructions) to measure density, specific gravity, and viscosity of three different liquids.

Upon approval of the protocol, conduct a set of experiments in triplicate to measure the density, specific gravity, and viscosity of three different liquids.

Document the experiment(s) into a laboratory report and address the following in the report:

Derive the fall velocity equation, starting from the force balance on the sphere and assuming that \(C_D=\frac{24}{Re_D}\)

Compare your results with tabulated values for density and viscosity for the three fluids.

Experiments are conducted in triplicate, so you can compute mean values and standard deviations; what does this information tell us about the accuracy of the measurements?, What does it tell us about the repeatability of the measurements?

What are some potential sources of errors in your lab experiments. Discuss in the context of measuring density, specific gravity and viscosity.

Warning

The protocol is evaluated to ensure that the envisioned procedures can be safely conducted under appropriate supervision. The experiments may produce incomplete results if steps are ommitted.

Deliverables#

Develop an experimental protocol (step-by-step instructions) to measure density, specific gravity, and viscosity of three different liquids. Submitted in advance for instructor approval - the protocol will become part of your laboratory report.

Laboratory Report documenting the actual experiments, and other required content including comparison to tabulated values.