Correlation (Causality's mimic!)¶

The literary (as in writing!) formulation of causality is a "why?, because ..." structure (sort of like if=>then) The answer to a because question, should be the "cause." Many authors use "since" to imply cause, but it is incorrect grammar - since answers the question of when?

Think "CAUSE" => "EFFECT"

Correlation doesn’t mean cause (although it is a really good predictor of the crap we all buy - its why Amazon is sucessfull)

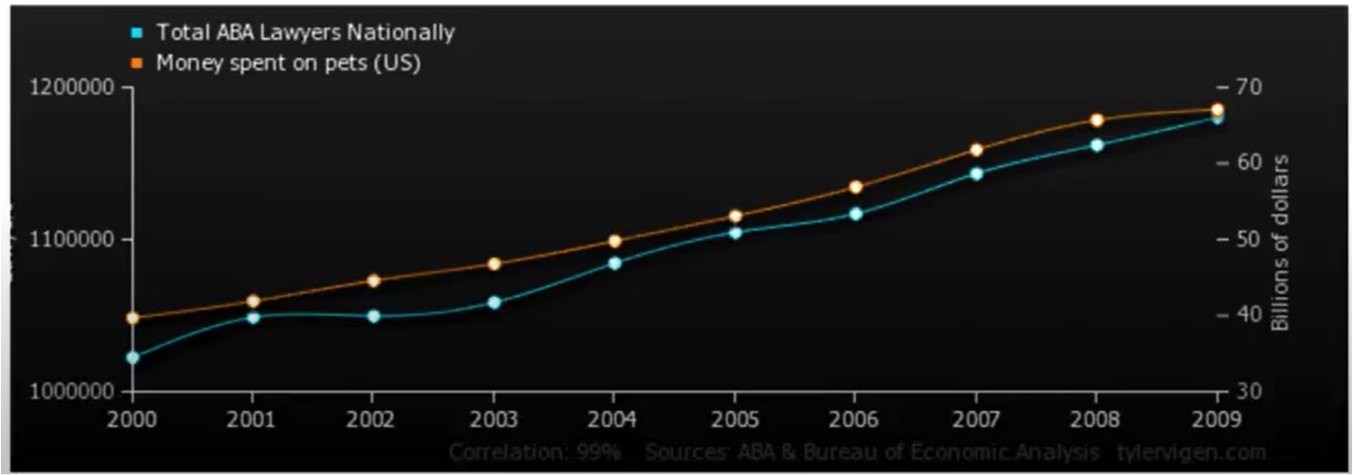

Consider the chart below

The correlation between money spent on pets and the number of lawyers is quite good (nearly perfect), so does having pets cause lawyers? Of course not, the general social economic conditions that improve general wealth, and create sufficient disposable income to have pets (here we mean companion animals, not food on the hoof) also creates conditions for laywers to proliferate, hence a good correlation.

Nice video : Correlation and Causation https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Sa2v7kVEc0

Taking some cues from http://water.usgs.gov/pubs/twri/twri4a3/

Concentrations of atrazine and nitrate in shallow groundwaters are measured in wells over a several county area. For each sample, the concentration of one is plotted versus the concentration of the other. As atrazine concentrations increase, so do nitrate. How might the strength of this association be measured and summarized?

Streams draining the Sierra Nevada mountains in California usually receive less precipitation in November than in other months. Has the amount of November precipitation significantly changed over the last 70 years, showing a gradual change in the climate of the area? How might this be tested?

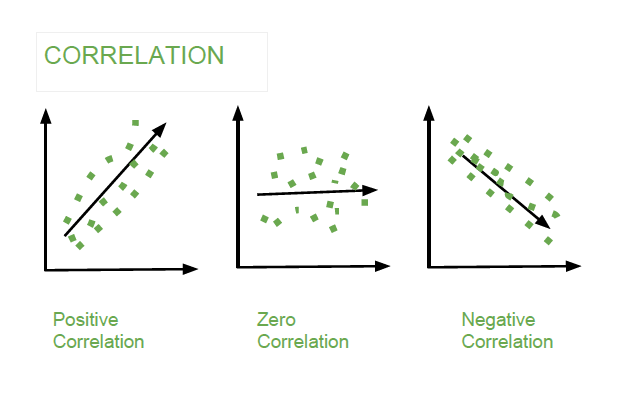

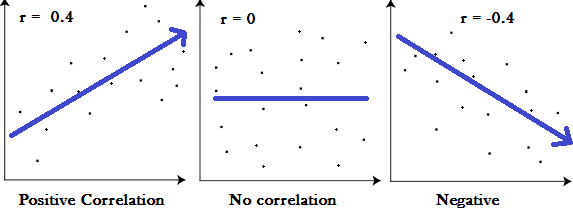

The above situations require a measure of the strength of association between two continuous variables, such as between two chemical concentrations, or between amount of precipitation and time. How do they co-vary? One class of measures are called correlation coefficients.

Also important is how the significance of that association can be tested for, to determine whether the observed pattern differs from what is expected due entirely to chance.

Whenever a correlation coefficient is to be calculated, the data should be plotted on a scatterplot. No single numerical measure can substitute for the visual insight gained from a plot. Many different patterns can produce the same correlation coefficient, and similar strengths of relationships can produce differing coefficients, depending on the curvature of the relationship.