The Dataframe¶

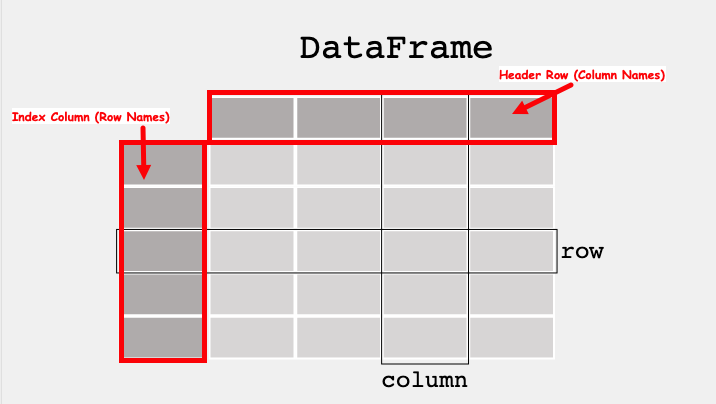

A data table is called a DataFrame in pandas (and other programming environments too). The figure below from https://pandas.pydata.org/docs/getting_started/index.html illustrates a dataframe model:

Each column and each row in a dataframe is called a series, the header row, and index column are special.

Like MS Excel we can query the dataframe to find the contents of a particular cell using its row name and column name, or operate on entire rows and columns

To use pandas, we need to import the module.