File system¶

In computing, a file system or filesystem, controls how data is stored and retrieved. Without a file system, data placed in a storage medium would be one large body of data with no way to tell where one piece of data stops and the next begins. By separating the data into pieces and giving each piece a name, the data is isolated and identified. Taking its name from the way paper-based data management system is named, each group of data is called a “file”. The structure and logic rules used to manage the groups of data and their names is called a “file system”.

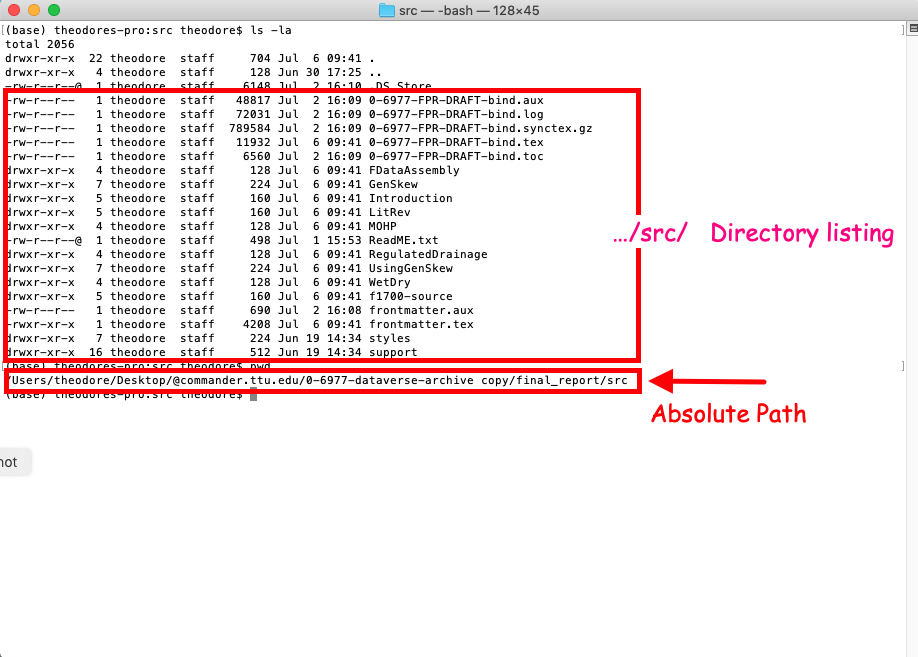

The figure below is a graphical representation of the filesystem on my office computer. I have the file browser listing the contants of a directory named /src. It is contained in a directory named /final_report, which is contained in a higher level directory all the way up to /Users (/ is aliased to Macintosh HD in the figure)

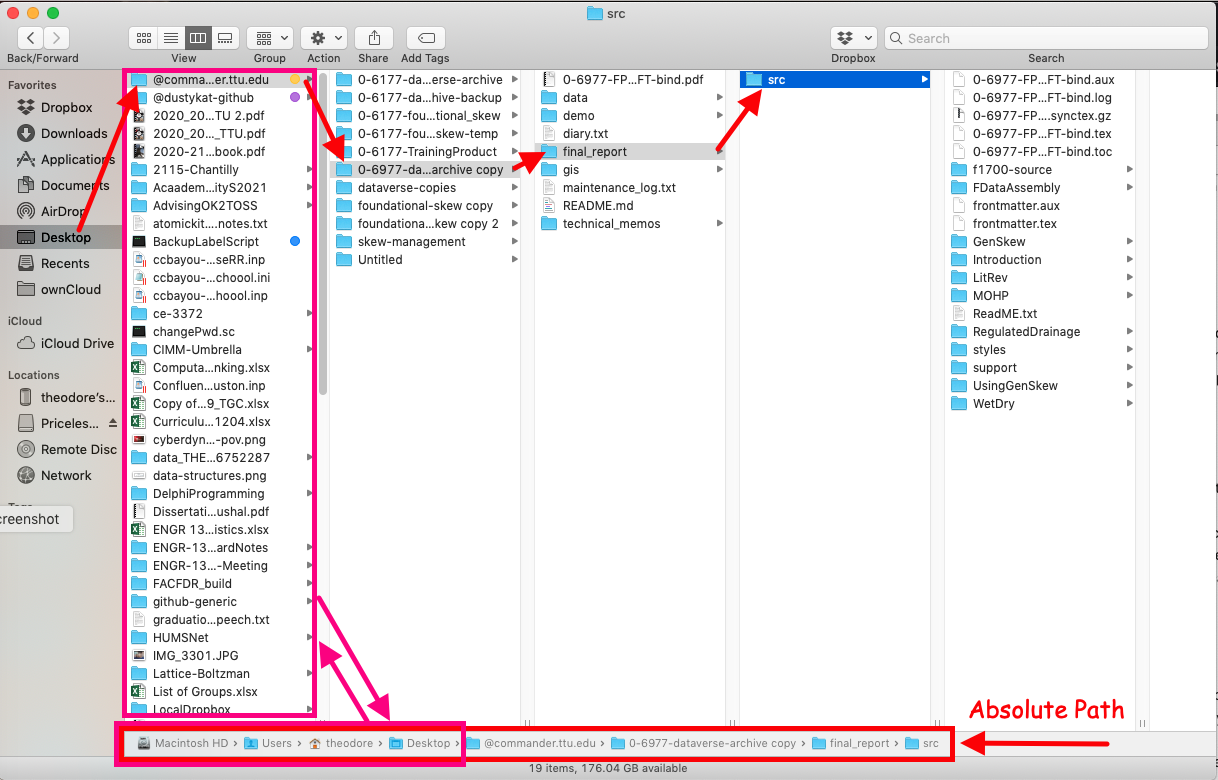

An equivalent representation, in a bash shell is shown in the figure below which is a capture of a terminal window.