Repetition and Loops¶

Computational thinking (CT) concepts involved are:

Decomposition: Break a problem down into smaller pieces; the body of tasks in one repetition of a loop represent decomposition of the entire sets of repeated activitiesPattern Recognition: Finding similarities between things; the body of tasks in one repetition of a loop is the pattern, the indices and components that change are how we leverage reuseAbstraction: Pulling out specific differences to make one solution work for multiple problemsAlgorithms: A list of steps that you can follow to finish a task

The action of doing something over and over again (repetition) is called a loop. Basically, Loops repeats a portion of code a finite number of times until a process is complete. Repetitive tasks are very common and essential in programming. They save time in coding, minimize coding errors, and leverage the speed of electronic computation.

Loop Analogs¶

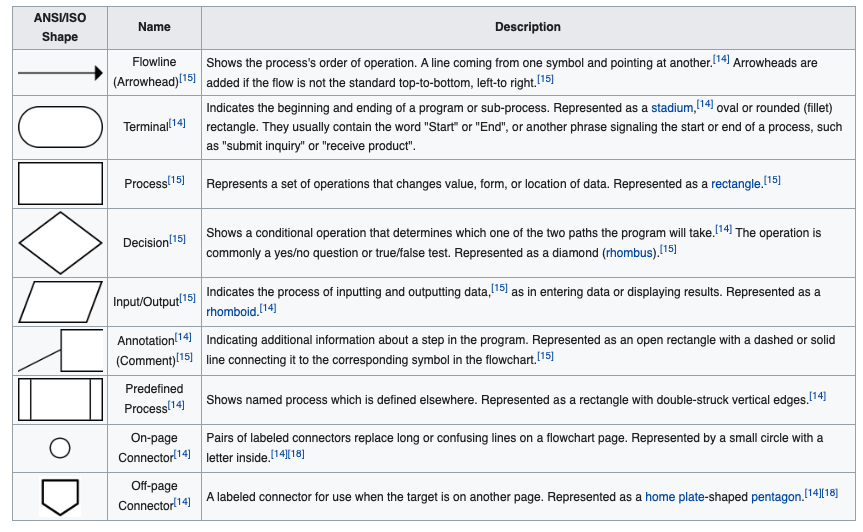

If you think any mass manufacturing process, we apply the same process again and again. Even for something very simple such as preparing a peanut butter sandwich:

Consider the flowchart in Figure 1, it represents a decomposition of sandwich assembly, but at a high level -- for instance, Gather Ingredients contains a lot of substeps that would need to be decomposed if fully automated assembly were to be accomplished; nevertheless lets stipulate that this flowchart will indeed construct a single sandwich.

| Figure 1 | Supervisory Flowchart Sandwich Assembly (adapted from http://www.str-tn.org/subway_restaurant_training_manual.pdf) | |

|---|---|---|

If we need to make 1000 peanut butter sandwichs we would then issue a directive to:

1) Implement sandwich assembly, repeat 999 times (repeat is the loop structure) (A serial structure, 1 sandwich artist, doing same job over and over again)

OR

2) Implement 1000 sandwich assembly threads (A parallel structure, 1000 sandwich artists doing same job once)

In general because we dont want to idle 999 sandwich artists, we would choose the serial structure, which frees 999 people to ask the existential question "would you like fries with that?"

All cynicism aside, an automated process such as a loop, is typical in computational processing.

Aside NVIDIA CUDA, and AMD OpenGL compilers can detect the structure above, and if there are enough GPU threads available , create the 1000 sandwich artists (1000 GPU threads), and run the process in parallel -- the actual workload is unchanged in a thermodynamic sense, but the apparent time (in human terms) spent in sandwich creation is a fraction of the serial approach. This parallelization is called unrolling the loop, and is a pretty common optimization step during compilation. This kind of programming is outside the scope of this class.

Main attractiveness of loops is:

- Leveraging

pattern matchingandautomation - Code is more organized and shorter,because a loop is a sequence of instructions that is continually repeated until a certain condition is reached.

There are 2 main types loops based on the repetition control condition; for loops and whileloops.