Example of Problem Solving Process¶

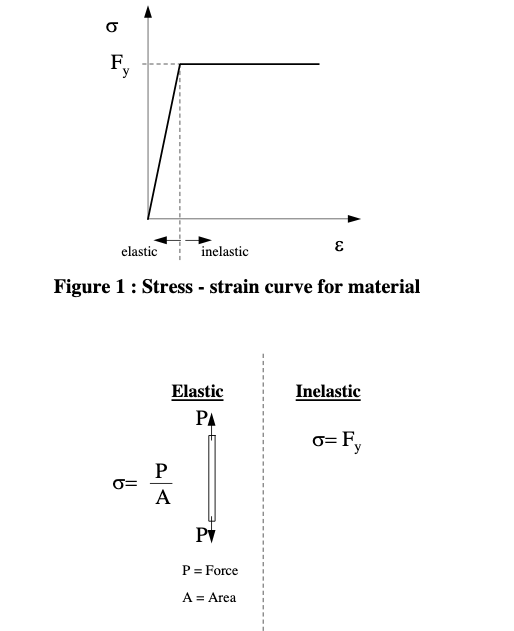

Consider an engineering material problem where we wish to classify whether a material is loaded in the elastic or inelastic region as determined the stress (solid pressure) in a rod for some applied load. The yield stress is the classifier, and once the material yields (begins to fail) it will not carry any additional load (until ultimate failure, when it carries no load).

Step 1. Compute the material stress under an applied load; determine if value exceedes yield stress, and report the loading condition

Step 2.

- Inputs: applied load, cross sectional area, yield stress

- Governing equation: $ \sigma = \frac{P}{A} $ when $\frac{P}{A} $ is less than the yield stress, and is equal to the yield stress otherwise.

- Outputs: The material stress $\sigma $, and the classification elastic or inelastic.

Step 3. Work a sample problem by-hand for testing the general solution.

Assuming the yield stress is 1 million psi (units matter in an actual problem - kind of glossed over here)

| Applied Load (lbf) | Cross Section Area (sq.in.) | Stress (psi) | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10,000 | 1.0 | 10,000 | Elastic |

| 10,000 | 0.1 | 100,000 | Elastic |

| 100,000 | 0.1 | 1,000,000 | Inelastic |

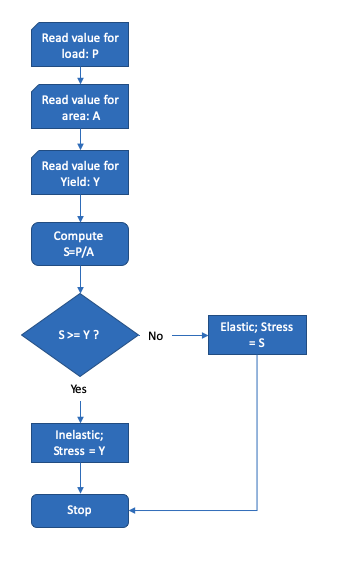

The stress requires us to read in the load value, read in the cross sectional area, divide the load by the area, and compare the result to the yield stress. If it exceeds the yield stress, then the actual stress is the yield stress, and the loading is inelastic, otherwise elastic

$$ \sigma = \frac{P}{A} $$$$ \text{If}~ \sigma >= \text{Yield Stress then report Inelastic} $$Step 4. Develop a general solution (code)

In a flow-chart it would look like:

| Flowchart for Artihmetic Mean Algorithm | ||

|---|---|---|

Step 5. This step we would code the algorithm expressed in the figure and test it with the by-hand data and other small datasets until we are convinced it works correctly. We have not yet learned prompts to get input we simply direct assign values as below (and the conditional execution is the subject of a later lesson)

In a simple JupyterLab script